The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe

As the ones who have read substantial articles about the Ottoman Empire from various European historians will certainly know, there is a European view of Ottoman history with is eminent in Europe and the West.

Historian and Ottoman-expert Daniel Goffman questiones this European view of Ottoman history. He gives an example Daniel Goffman says: ‘One chapter in a recent history of the Ottomans begins with the assertion that “the Ottoman Empire lived for war.” Goffman quickly adds ‘This indeed is a damaging and misleading stereotype.’

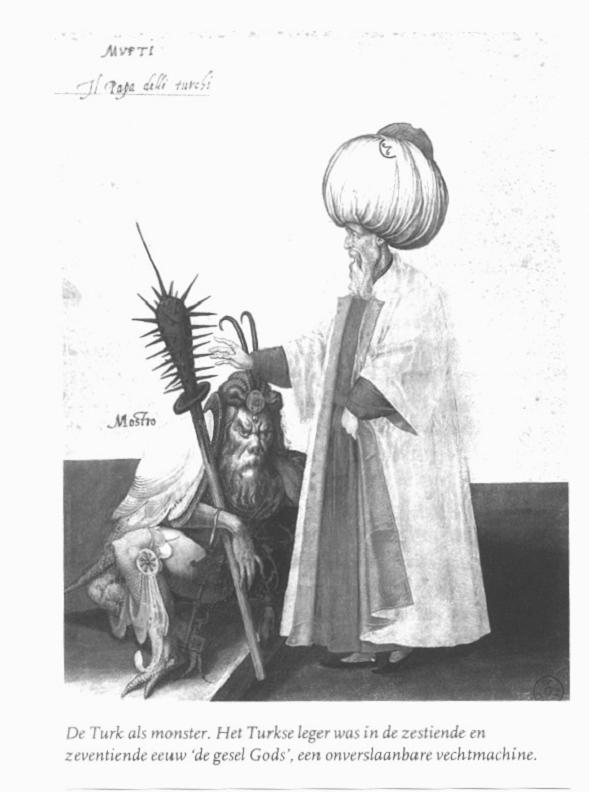

As additionel prove we can look at this picture about ‘The Turkish Monster in the sixteenth and seventeenth century’. The artist also wrote that ‘The Turks are a fighting force send by God himself to punish us, the Europeans’:

Goffman continues: ‘Did the European states somehow not life for war? Suicidal crusades, Christian children send on crusades and numorous wars among the Europeans’ are just a few examples of the importance of war in Europe. According to Daniel Goffman the Ottomans can also be seen as: ‘the founders of a new and liberating empire, providing a save haven for runaways from a fiercely intolerant Christian Europe. For whereas in the Ottoman world there were thousands of Christian renegades, but one almost never discovers converts from Islam in Europe.’ Indeed when I got to think about this sentence, I took the map of Ottoman Europe and as we can all see, the countries conquered by the Ottomans were never made Muslim. As we can see here, the majority of the people in these countries were and are still Christians.

Daniel Goffman states that ‘the Ottoman Empire saw itself as an European Empire, for example it adopted much of the Byzantine tax structure and customary law which they blended into sultanic law as a complement to Islamic law.’ I think this is only partly true, because there are a lot of elements in the Ottoman world that are not European, but Central-Asian, Persian and/or Arabic. In my opinion the Ottomans saw themselves as much an European society as a Middle-Eastern or Central-Asian. They were not to afraid to take over any elements they accountered in either Europe or the Middle-East, from which they could benefit.

In an other passage Goffman says: ‘while it was virtually impossible for Muslims to trade and reside in most Christian lands, European Christians could live in many Islamic societies as “People of the Book,” that is, as those who heeded the sacred writings of Judaism, Christianity, or Islam.’

This was possible because in the Kuran it says that Christians and Jews are believers who are “temporarly confused or badly corrupted” and that they, with time, will come to their senses and choose the one and only true religion Islam. Also the Islam includes many aspects of Christianity and Judaism, for example Islam consideres the prophets Abraham, Mozes and Jesus messengers of God aswell.

According to Goffman a second factor was that these ‘political as well as religious practices remained more Central Asian than Middle Eastern.’ Because we can see the same treatment in the Empires of the Mongols, Selçuks and Mamluks. All were Central Asian Turkic people and did the same in the case of freedom of religion.

However this did not mean that the Ottomans were not as religious as other Muslims like the Arabs or the Persians. On the contrary, ‘the early Ottomans and other western-Anatolian Turks had converted to Islam at some time during their migrations across Central Asia, Persia, and Anatolia and had become dedicated, even fanatical, warriors on behalf of gaza (what means holy war).’

As a matter of fact the first Ottoman rulers were not called sultan but Gazi (what means holy warriors).

Goffman has an explanation for this happening: ‘the newly converted is often the most passionate of believers’. We see this with Emperor Constantine in the Roman Empire and the Franks, who become Christians as well as with Arabs under prophet Muhammet and Central Asian Turks turned Muslim.

‘Combine these dedicated and fanatical warriors with the political and military brilliance of the first Ottoman leaders, Osman, Orhan, Murat, and Beyazit and the vulnerable time and place for the Byzantine frontier who were sacked by Latin crusaders in the early 1200’s and you will have an rising Ottoman Empire’ as Goffman states.

Historiographical debate that threads its way through and beyond the twentieth century: Was the Ottoman Empire a legacy of the Byzantines, the Arabs, or the Central Asians?

A fine example from how the different cultures influenced the Ottoman Empire is the harem. The legacy of acquiring women through “raids” most likely came directly from a central Asian tradition; the employment of polygyny, that is multiple wives, probably derived from Islamic sources; the Ottomans may have learned of concubinage from the Persians; and they may have adapted from the Byzantines the idea of securing alliances and treaty through marriages. This would explain why all the Sultans except Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi, had non-Turkish, non-Muslim mothers and wives.

Another example is the Janissary Corps, this was an army of Christian soldiers who were trained and converted to the Islam from an early age on, as early as five or six years old. This idea of a slave army came from the Arabs who pushed into Central Asia in the eighth and ninth centuries under the Abbasid dynasty, were they enslaved, converted and trained non-Muslim Turks. These Turks would later take control of the Arab world as the Mamluk Empire. But what the Ottoman Turks added were the young age of the slave soldiers, probably from the Central Asian tradition where the military training began at a very early age. The policy of devşirme, or collecting young Christian boys from the Balkan region, as a tax came from the Byzantine tax system which also pressured the local peoples to pay their taxes in either money or products.

The religious and political elite in the Ottoman Empire, or ulema, came together in the so-called Divan. What was to be compared with the Kurultay of the Mongol Empire.

Military innovation as well as religious flexibility helped consolidate the Ottoman state. The Ottoman state granted much of the conquered territories to its warriors. When the government distributed land and villages to warriors, these warriors thus became sipahis. The lands they received were called timars. The sipahis were also called beys and the Ottoman government appointed Sancakbeys over the sipahis. Sancakbeys in their turn had a beylerbeyi or provincial governor to answer to.

According to Goffman: ‘These sipahis hardly existed in Arab lands, because the Ottomans understood historical and political peculiarities, and never brought Egypt into as tight administrative control as Hungary’. This proves the state could be bloodily harsh, or astonishing leniency as the situation demanded.

The hightigh of the Ottoman Empire accured under the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, or Kanuni Sultan Süleyman like the Turks today recall him, what means Süleyman the Lawgiver. This nickname came from the fact that Sultan Süleyman codified the Ottoman legal code during his reign.

In Süleyman’s reign the great architect Sinan, a devşirme boy who began his career as a designer of military bridges, became the imperial architect.

Also during Süleyman’s reign in the sixteenth century, began the struggle between the Catholic world and Protestants. Many protestants understood that only the Ottoman diversion stood between them and obliteration. This went as far as alliances between the Ottomans and the France aswell as the Dutch. This led to the wintering of an Ottoman fleet in French Toulon in 1543 and Dutch Zeeland in 1599.

During those troubled decades, the empire also became a haven for the religiously oppressed. According to Goffman: ‘minorities in the Islamic state constructed by the Ottomans lived more comfortably and with less fear then they did in rival European states, even than they do in the modern secular state.’

After the reign of Süleyman the Empire started to decline. As the wars started to end, the Janissary corps still had to be paid, war or no war. So as a consequent the Janissary corps were allowed to work, marry and have children just like other civilians. So it came that the Janissaries loyalty no longer went to the Sultan but rather to their own families, children and jobs.

But as Goffman says: ‘because the Ottoman Empire not only survived these crisis, but prelonged their Empire for another hundreds of years to come. We must view and understand the creativity, endurence, and willingness that brought the Ottoman Empire to the 1920’s’.

In short: I agree with Daniel Goffman that the Ottoman Empire was not a barbaric Empire, like some European historians claim, but instead an Empire far more developped than their European counterparts.

Armand Sağ

5 december 2005

© Armand Sağ 2005

|